Artefacts and Relics discussed by Tissot

First - what are the issues with relics?

In the research for his books, Tissot has clearly done a lot of research into documents and, it would seem, extracting or absorbing stories and traditions from many religious communities. There are many artefacts, which may be called relics, that are pivotal to the life of Jesus and surrounding the Passion in particular. The word relic is more commonly used when a physical part of a holy person is being described, such as a skull or a finger, though it sometimes also used for things with which a holy person has been in contact. First, a warning about relics.

A problem with relics

You do not need relics for salvation. You can, for example, find what you need for salvation in the Bible; it is not the only place you can find it, but it is a very good place and not hard to find. The early Christians had the Jewish scriptures and then quickly the 'memoirs of the Apostles' as Justin Martyr puts it in 158 AD, which is a way of expressing what we now call the New Testament. Most of this was written prior to 70 AD. There is much recent and persuasive narrative on this, such as here, and it makes complete sense not least because the destruction of the Temple is not mentioned, nor is Saint Paul's fate at the hands of Nero, and Luke and Acts clearly flow together. Plus there were some deutero-canonical books that were, at least, 'highly valued' (a longer debate ensues, but the deutero-canonicals such as Judith were printed in everyone's Bibles until the 19th century). In addition to this written treasure, oral tradition contains a parallel and large source of material and was also extremely important in the early years of the Christian Church. Together with scripture these give us the deposit of faith. The writings of the church fathers also give us firm ground, which reinforce and expand the interpretation of biblical sources and which help to document otherwise oral tradition. Such evidence is persuasive and robust. I say all this because I want to put relics second, or in a different class, to these sources.

Relics can provide an enormous benefit, because we are material creatures, created so by God and to be so in the next life, and we rely on our senses to inform our imagination and to verify reality. It is hard to use our senses on material that is very distant in space and time. If we are presented with a relic, we are confronted with an inescapable fact of this or that person’s existence or experience, directly through our senses, with the gap of time and space suddenly removed. It must be fair to say that relics might also contain some spiritual property, as we know that Saint Paul’s handkerchiefs could heal people, and it may be that repeated veneration of the relic increases this property, though spiritual properties are much less perceptible for most people. The main effect of a relic in my opinion is that it is like a slap in the face to your intellect - a brute fact of a huge and serious inheritance of facts and faith. You may not simply turn your eyes inward to your own cherished beliefs when confronted with it, instead you are invited to open your mind and place yourself at the scene. It can be very humbling and intimate.

So what could be wrong with them? I started by saying you do not need them for faith. “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed” (John 20:29). The real issue though is that they can be faked, and it seems that this has been quite common through history. There is money to be made from the faithful or from the honour of possessing or giving a relic, and nobody knows exactly what the original looks like. I have seen some commentary to the effect that ‘well if it gives people spiritual peace or strength and encourages devotion, then does it really matter?’ (e.g. here and here). Well, in the spirit of James Tissot, it matters to me quite a lot. He has applied thought to some important relics in the course of his studies. Fake relics could lead people to doubt their faith, or their faith leaders, later on, after their initial excitement and joy has dies down. Critics of the faith may seize on it. Once these things are set aside, then of course there is value in something that allows contemplation of the events that changed the world so fundamentally, and, for believers, gives them something tangible to remind them of the sure and certain hope of the kingdom of heaven and earth to come, and freedom from the chains of this broken world.

So, when approaching artefacts, disappointment should be guarded against.

On the other side of this, there can also be surprise and rejoicing when a genuine new relic or archaeological artefact is found, such as in the case of the cylinder of Nabonidus that verified facts about Balthazar written in the book of Daniel that were previously doubted. I went to the British Museum to see this first hand after reading John Lennox's epic book explaining the Book of Daniel, one of my favourite books of the Bible - Daniel and his friends are obedient and productive slave-citizens in Babylon, but time and again they put their lives on the line when asked to dishonour God. On the whole, however, there are a huge number of relics and my own light reading on the topic leads me to think there are a lot of fakes.

There may be an intermediate case where a relic is copied deliberately and not intended to deceive anyone. Today, it is very common for museums to display copies of important works rather than the delicate original, or for large pieces of masonry to be reconstructed around some original fragments. Having copies mean the 'reality' of the item can also be presented to more people, without any deceit intended.

So, I think it is wise to be wary of relics, and to think carefully about whom to trust on such matters. If you do not need to take a position on something, be happy accepting and considering the matter as it stands. Do trust sometimes though, or your life may be impoverished.

What relics or artefacts does Tissot discuss?

The following relics or artefacts are discussed by Tissot in relation to existing, known relics; he discusses other artefacts, such as the seamless garment worn by Jesus on Good Friday, but without relating them to items venerated today:

- The stone pillar at the Judgment Hall of Caiaphas, to which Jesus was chained during the early hours of Good Friday.

- The pillar of flagellation, i.e. the pillar to which Jesus was chained to be whipped or scourged.

- The veil of Veronica.

- The Crown of Thorns.

- The Title on the Cross.

The Stone Pillar to which Jesus was tied at the Judgment Hall of Caiaphas

In short, Jesus of Nazareth was chained to this pillar.

'Pillar of Flagellation', Church of Santa Croce de Gerusallemme

(Wikipedia)

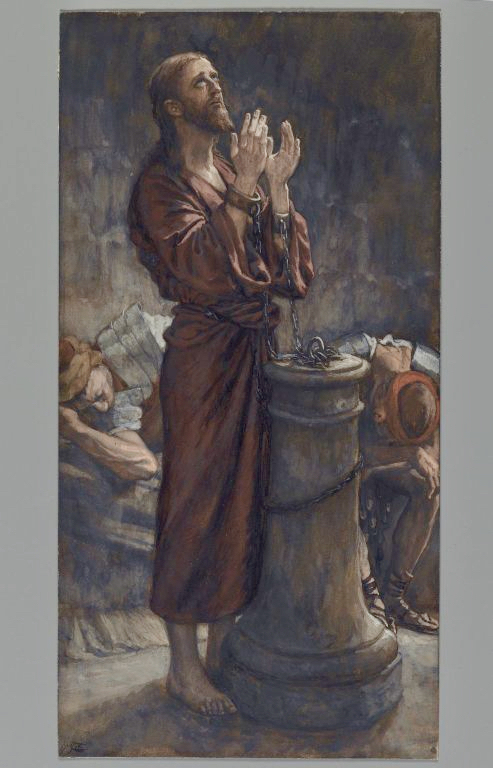

Tissot's reconstruction - 'Friday morning - Jesus in prison'

Tissot has researched this pillar and a different pillar described below, and has come to the conclusion that the black and white pillar shown above is the pillar linked to his detainment in the early hours of Good Friday after being condemned in the Judgment Hall of the Sanhedrin. It is therefore exceptionally precious. As Tissot says "We have represented Him bound to a short column, and certain slight marks on it lead us to suppose that the column is the very one still preserved in the Church of Saint Praxedes in Rome." The pillar is commonly called 'the pillar of flagellation', but there is a rival for that claim.

Tissot (and others) conclude that pillar to which Jesus Christ was actually tied and flogged or scourged is a brown stone pillar of which there are now at least two pieces, one of which is in Jerusalem as described below. It is difficult to imagine that the height of the column shown above is sufficient for someone to be held firm for flogging, in contrast to what seems to be a much taller column represented below. Yet it is surely a pediment of such weight that it could not be moved by the detained person.

The Pillar of Flagellation

Tissot states: "Every Court of Justice had its scourging column... Saint Jerome tells us that he saw the Column of Scourging in the porch if a church at Sion; some fragments of this Column are reverently preserved in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem and others ... at Madrid, Venice and elsewhere." At the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is a well-venerated portion of pillar that many believe to be the pillar of flagellation, made of red porphyry. Another portion of column at the Patriarchal Church Of St. George in Istanbul is also claimed to be part of the column of flagellation. Tissot refers to other potential relics at Venice and Madrid. I don't have any reason to doubt his conclusions.

Again, these are extraordinarily precious items.

Portion of column at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem

Tissot's reconstruction - 'The Scourging of the Face'

Portion of pillar at Saint George's Orthodox Church at Fener, Istanbul

The Crown of Thorns

Before reading Tissot's book, I watched a report on the procession of the most famous and well-respected 'Crown of Thorns' held in France. What I could see clearly, and hear from the narrative, was that the crown was composed of something like rushes, and seemed absent of thorns. The way the Crown was presented in a decorated glass case on a cushion gave the impression of thorns, but there seemed to be none physically present. This seemed very puzzling to me, that not one should be present. Tissot explains a widely held narrative that the thorns have, over time, been removed and given to churches around the world. A thorn from the Crown would perhaps be one of the most powerful relics that could be conceived; these touched Jesus Christ and some would bear His very blood, and are powerful symbols of suffering. I think the Crown also recalls the ram of sacrifice that God provides for Abraham on the same mount nearly 2,000 years earlier, since its head was caught in a thicket (Genesis 22:13).

This website gives a recent and clear explanation of the history of the Crown of Thorns, though it does not contain reference documents; Wikipedia gives similar details and I have not researched it further. The main body of the Crown is a sea rush circlet that is preserved at Notre-Dame and which is believed to have been passed to Saint Louis (King Louis IX) after being in Constantinople for centuries.

Tissot's witness is consistent with the history given at the above website and he speaks confidently on the topic, which carries weight. Tissot is quite open to criticising unreliable sources (for example on p263 of Volume II, Tissot blasts certain authors who claim that there was only one, not two, miraculous draughts of fishes). The Crown of Thorns is worthy of further investigation, in particular more information about the fate of the thorns and their biology, but I have come to be persaded by Tissot's opinions on almost all of the topics he covers.

The Title on the Cross

The Gospels are absolutely clear that Jesus was crucified beneath a sign that displayed his alleged crime. All four Gospels record this, as you can easily see here which is part of a very helpful side-by-side comparison of the Gospels - thank you Jo Edkins!

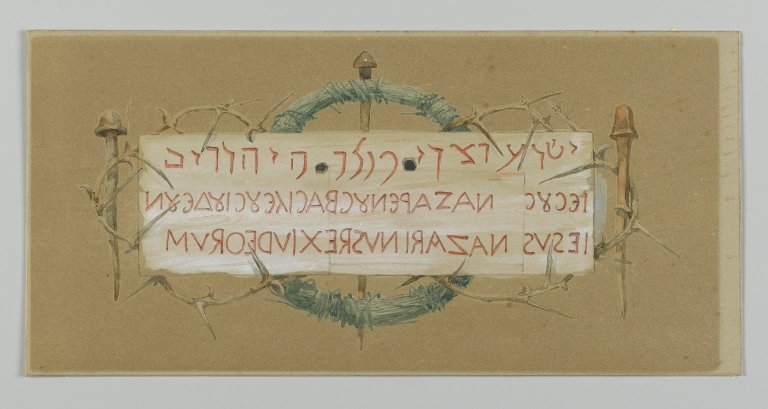

John the disciple (or Apostle, or Evangelist) is very commonly held to be the only one of the twelve disciples at the foot of the cross, in fact 'the beloved disciple' who represents all believers, though some hold that his witness is complemented by another John 'the Elder'. He also wrote his Gospel last, and likely with a view of the other Gospels, so it is understandable that he be more precise in certain matters such as this, and he writes the words out in full "JESUS OF NAZARETH KING OF THE JEWS", saying that this was written in three languages - Hebrew, Greek and Latin - by order of Pilate (John 19:19) who was particular about the words.

The relic shown below and held at the Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome first appears in 1492 along with the account that it was sealed in the wall of a church between 1122-1144 because it was in a box with the seal of Cardinal Gherardo Caccianemici of that time. Prior to that there is some mention of such a relic in Jerusalem but only after the death of Saint Helena who was supposed to have brought it to Rome. The provenance is weak, and it is against a backdrop of high levels of forgeries in the middle ages, going by most commentaries.

The relic said to have been brought from the Holy Land by Saint Helena and now held at the Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome

Tissot's reconstruction. Note the thin vertical lines at about 40% and 85% from the left, which are obviously representing the edges of the title relic shown on the left.

The wood has been radio-carbon dated to 996-1023 AD as you can see in this concise paper here. I have seen arguments made that you can't trust such techniques if the sample is weathered or left in the sun and so forth, but the linked paper also tests a very weathered counter-example known to be about 2,000 years old with no problem. Arguments looking to debunk an unwanted outcome are to be treated with scepticism; if the result had turned out to date the wood from the first century, nobody would be claiming the technique might be out by a thousand years.

The work could be a 'genuine' copy, i.e. done with good motives as discussed above. This would be plausible at first glance. I find that two problems emerge, however.

(1) The Greek and Latin words are written right-to-left ('retrograde'). I have nowhere seen any good explanation for this. There are bad ones, such as here "Since the Hebrew language is written right to left, the other two languages are also written in this way" - surely a non sequitur, since each line is surely written for a different audience. In a few situations, apparently, writers would wrap a sentence or flow of text from right-to-left after it had begun left-to-right and reached the end of the substrate so that the eye moves back more easily along the letters (called 'boustrophedon'), but that is not the case here. This commentator is similarly very sceptical, and this book states that retrograde Greek writing in stone was rare until near the end of the 6th century. Another detailed source touches on it but does not speculate as to the likelihood of a first-century inscriber writing retrograde. I can speculate a reason, that the signwriter, having written Hebrew first, wanted to make sure that the Greek and Latin didn't then spill over the right side of the wood, but it surely takes little effort to sketch it out first on your wood before you write anything at all. Tissot suggests the writers of the Title would have been Jewish, which is logical if the Romans struggled to write Hebrew, though I would like to see more evidence to support such an important part of the Roman - pointedly not Jewish - execution process being given to Jews. Jesus had earlier ridden into Jerusalem with thousands of cheering supporters and was very well known and, on the face of it, a serious threat to law and order. The Jews were indignant that those precise words be used and Pilate said 'What I have written, I have written' - so, would he really pay no attention, or allow it to be written backwards? I will be open to a good justification for this issue, but from my own research there is scholarly silence.

(2) The order of the languages is different to the Gospel of John, the eye-witness. In what seems to be to an acrobatic use of logic, it has been put forward by an expert that this means there is no doubt that it is genuine, after all a forger would slavishly copy the words of the Gospel. Here, we are told that two experts think that 'a variation of John 19:19 is a freedom no forger would ever risk'. That is not a good argument - all it takes is for one forger to realise that people are taken in by mysterious idiosyncracies - surely something that adds mystique to the item - and they introduce what seems to be an error so that people will exclaim how authentic it is. Nevertheless the argument is made in a number of places and it is hard to be persuaded.

In conclusion, the relic is surely either a forgery or a copy made around 1000 AD. If it was sealed up in the wall of a church then it suggests that it was valued by those holding it at the time, as you would be less likely to make such an effort for a forgery, though I have not seen the evidence surrounding its discovery. The backwards writing is indeed a mystery and not the kind that deepens your faith, just puzzling. I don't trust it, but it gives a way of contemplating the crucifixion and the importance of those words, and that is clearly a massive source of spiritual strength for many, many people. If you believe enough to make the pilgrimage just in case it is true, or because you want to offer up a part of your life, your will and your body to Our Lord, then you have faith, and God bless you. Let us dwell on that and on our loving Saviour whom we all crucified under this sign in AD 33 through our sins, and who loves us without measure.

-